A gauzy lassitude blankets men’s tennis this week, which also happens to be Roger Federer’s 286th week as the world’s top player. Admittedly the degree to which one finds it smothering will depend on your preferences regarding the top players, and towards those already reapplying themselves in Stuttgart, BÃ¥stad, Umag and Newport. Fans of the new No.1 are doubtless content to bask and purr a while longer. Fans of Cedrik Marcel Stebe have been looking forward to this short stretch all year, this tiny assortment of clay tournaments so inconsequential that it defies even the ATP’s attempts to market it badly. This is Stebe’s time to shine. These few clay tournaments, wedged artlessly between Wimbledon and the US hardcourts, have never made a great deal of sense , assuming that sense is something a tennis calendar has to make. With the grass court Olympics only weeks away, they make even less sense.  Still, BÃ¥stad is worth tuning in to merely for the setting, as attractive as anywhere on the tour, although it is, sadly, exactly one Robin Soderling short.

Still, Båstad is worth tuning in to merely for the setting, as attractive as anywhere on the tour, although it is, sadly, exactly one Robin Soderling short.

Assuming Novak Djokovic doesn’t scrounge up 76 ranking points in the next ten days, Federer will next week break the all-time record for weeks at No.1, currently held by Pete Sampras. Already this week he has apparently achieved some kind of record for consecutive media appearances. I know this because a number of media reports have now appeared to tell us how much media Federer is doing. You know it’s a slow week when the media starts marvelling at itself. And now I’m marvelling at that. Before ennui overwhelms us all, I’ll marvel at something else. I’ll say random things about Wimbledon.

Nary a Dry Eye

‘Ladies and Gentlemen, the Wimbledon Gentleman’s Singles Champion 2012, Roger Fereder!’ It was a mystery why the MC duties for the men’s final trophy presentation were given to someone who apparently doesn’t follow the sport. He sounded far too old to be the work experience kid.

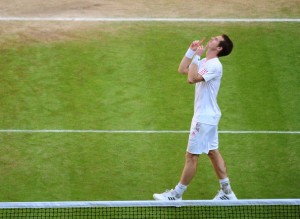

Aside from that, the presentation had its share of stirring moments, depending on one’s tastes. Sadists who relish the spectacle of a lean Scotsman falling to collect himself for a painful eternity – a niche fetish, as these things go – were well served. Murray remained unmade for an uncomfortably long time, which rendered his eventual rally all the more poignant, especially when he broke down again upon thanking his supporters. The unsayable Roger Fereder bestowed a hug on him after that, with the free arm that wasn’t clutching a hefty, pineapple-themed trophy. He was Single Handed Champion of the World, after all.

Wanting, and found tested

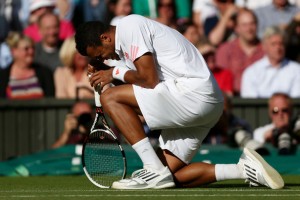

Reproducing last year’s success was always going to test Bernard Tomic. In 2011, as an 18-year-old, he became the youngest Wimbledon quarterfinalist in 25 years. Losing in the first round as a 19-year-old turned out to be an altogether lesser achievement. The Australian media proved typically eager to explore the difference fully, presumably as a way of coming to terms with the despair induced when no other Australians progressed past the second round. Lleyton Hewitt, as always, had just suffered a bad draw. Sam Stosur, the world No.5 and reigning US Open champion, had outdone herself merely to win a round on grass. But Tomic was the great hope. Wasn’t he supposed to be No.1 by now?

Tomic quickly conceded that he hadn’t done enough work, and that he was entirely to blame for the desultory loss to David Goffin. (It wasn’t reported to what extent Goffin agreed with this assessment.) This tallied well with the prevailing local sentiment – tales of squandered potential play well here – and so he was subsequently applauded for his contrition, and held up at least once as an example of how honest self-appraisal will reveal the clear path forward, a perfect example of confusing words for deeds.  It is to Tomic’s credit that he has worked hard enough elsewhere that while his ranking has dropped, it hasn’t been cataclysmic. He remains in the top 50, for now, but securing a US Open seeding will require more than good intentions, self-flagellation and cunningly wrought strategies. He’ll probably have to win some matches on the US hardcourts.

It is to Tomic’s credit that he has worked hard enough elsewhere that while his ranking has dropped, it hasn’t been cataclysmic. He remains in the top 50, for now, but securing a US Open seeding will require more than good intentions, self-flagellation and cunningly wrought strategies. He’ll probably have to win some matches on the US hardcourts.

Milos Raonic has demonstrated a knack for winning matches on US hardcourts, although he traditionally flourishes earlier in the season, preferring to spend the summer recovering from hip surgery. What he hasn’t demonstrated is a capacity to win on the Wimbledon grass, in direct contravention of everyone’s stentorian pronouncements that he should never lose. He was probably unlucky to discover a resurgent Sam Querrey this year, but top players are top players because an unlucky early round match is merely testing rather than disastrous (with notable exceptions). Plenty of people selected Raonic as their outside shot at winning the title, assuming the top three were otherwise indisposed. Failing that, it was at least expected that the Canadian would progress the farthest of all his peers. I suppose he did, so long as you don’t consider Goffin a peer, on account of him being, um, Belgian. Like Grigor Dimitrov and Ryan Harrison, Raonic progressed all the way to the second round. Once there he not only finished his match (unlike Dimitrov), he actually won a set. The sky is the limit, of course, but it’s still the sky, and far away.

Brian Baker is 27, and therefore the oldest youngster in world tennis right now, with the possible exception of Tommy Haas. Baker reached the fourth round, where his dream run was cut short by Philipp Kohlschreiber, who was historically more likely to facilitate other player’s dreams by losing spectacularly. Baker has now proved he can play on clay and grass. It’s hard to imagine he can’t perform on US hardcourts, especially since he isn’t playing in the Olympics, and will be able to feast on anaemic draws laid out across the breadth of the continental United States.

The quiet American is now ranked No.76, and thus he won’t have to qualify for the US Open. Direct entry will undoubtedly seem like a bewildering luxury to Baker, who has grown accustomed to turning up at tournaments a week early, although it’s probably more accurate to say he still isn’t used to turning up at all. He will end the year inside the top 50, mark my words.  Assuming his body holds together – his name is a by-word for physical sturdiness – then it is entirely possible that he could be seeded for the Australian Open. Imagine that. But I’m getting ahead of myself.

Assuming his body holds together – his name is a by-word for physical sturdiness – then it is entirely possible that he could be seeded for the Australian Open. Imagine that. But I’m getting ahead of myself.

Spun Gold

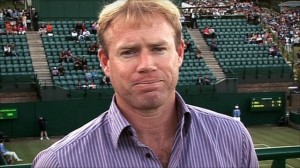

My favourite commentary moment came from Mark Petchey, a man who once comforted us with the news that ‘We now have so many memories we can never forget’. This unforgettable memory came while Petch was sharing a booth with John McEnroe and Tim Henman, although I cannot recall the match they were calling. One of the players executed a fine volley, which I suppose is remarkable enough given the current state of the tour. This was Petchey’s cue to launch into a disquisition on the finer points of volleying technique. Henman’s prowess at the net was fundamental to his perennial top-ten ranking. McEnroe’s forecourt genius propelled him to No.1, and seven major titles. Petchey peaked at No.80, which is respectable, but hardly comparable. He never broke into the top 100 in doubles.

It was rather like seeing someone stumble into the grandmothers-only session at an egg-sucking convention, only to knock down the key-note speaker and snatch away her microphone.

It was delightful.

A Smacked Gob

In January we marvelled when Leander Paes and Radek Stepanek defeated the Bryan Brothers to snatch the Australian Open doubles title. Jonathan Marray and Frederik Nielsen have won Wimbledon, thereby surpassing at a canter that earlier achievement, if only for sheer audacity. Four of their six matches went to five sets. Quite incredibly, their only straight sets win came against the team of Karlovic and Moser, which was also the only match that didn’t feature a tiebreak (the others all featured at least two each). Marray and Nielsen defeated the Bryans in the semifinals (6/4 7/6 6/7 7/6), and Lindstedt and Tecau in the final. This is the first career title for both of them.

Like the rest of us, they still cannot believe it.