Several hours ago, the clocks in London reached midnight, and Roger Federer commenced his 287th week as the planet’s highest ranked tennis player. As with so much else, he is the only man to have done this. As I write, Federer’s clothing sponsor Nike has released a limited run of recoloured Zoom Vapor RF shoes. There are 287 pairs, and each costs $287. I expect Nike’s online store crashed within seconds.  This probably isn’t the most important record that Federer holds, but it the one that somehow remained tantalisingly near even as it receded agonisingly, and thus the one by which his fans would most readily be reduced to gibbering incoherence. It is, consequently, kind of a big deal.

This probably isn’t the most important record that Federer holds, but it the one that somehow remained tantalisingly near even as it receded agonisingly, and thus the one by which his fans would most readily be reduced to gibbering incoherence. It is, consequently, kind of a big deal.

The first 200 or so weeks were easy. Once Federer had ascended to the top spot by defeating Juan Carlos Ferrero in the semifinal of the 2004 Australian Open, displacing Andy Roddick, he rapidly built and maintained a points-lead so vast that it was almost without precedent. By the conclusion of that year the question was already being posed seriously of how he might ever lose, even injured. The documentary of the Tennis Masters Cup for that year was called Facing Federer, with the implied subtitle being ‘Why Bother?’ He had spent less than a year at the top, but his position there already seemed eternal. There was just that quality to it, such that few even doubted whether he would be able to back it up in 2005. In any case, it turned out no could face him in Houston, and he ended the year with almost double the points of the No.2, who for the last time was Roddick. Federer was on a finals winning streak that would last another year, and would eventually extend to 24 straight victories.

Rafael Nadal ‘arrived’ in 2005, for many fans seemingly from nowhere, although he had finished 2004 at No.51, having snared his first title in Sopot, Poland. (A perusal of Wikipedia suggests that this is among the more fascinating things to have happened in Sopot, although I note it also boasts the longest wooden pier in Europe, and has been sacked by every passing army.)  With the Sopot pier acting as some kind of springboard, Nadal would attain the No.2 ranking in July of 2005, and remain there for 160 consecutive weeks, which remains a record. Federer and Nadal would occupy the two top spots for over three years, long enough that this configuration came to feel like a structural requirement of the sport, if only to casual fans.

With the Sopot pier acting as some kind of springboard, Nadal would attain the No.2 ranking in July of 2005, and remain there for 160 consecutive weeks, which remains a record. Federer and Nadal would occupy the two top spots for over three years, long enough that this configuration came to feel like a structural requirement of the sport, if only to casual fans.

In January of 2008 Federer arrived in Australia to the strenuously asserted revelation that his ranking was somehow at risk. The numbers had been crunched, and it was discovered that if Nadal won in Melbourne and Federer failed to reach the quarterfinals, then they would swap positions. Without exception, every interview was now about that. Federer was visibly irritated by this line of questioning, and on the face of it, it did seem ludicrous. In 2007 he had, again, won three of the four majors, and had reached the final of the other one. He’d finished the year with another dominant victory at the Masters Cup. And yet he was somehow one lousy day away from losing No.1. In order to ensure this wouldn’t happen, he promptly contracted glandular fever, and fell in the semifinals to Novak Djokovic. The extent to which these two events are related remains a subject of debate, but not a terribly interesting one.

Federer’s results were relatively poor through the US Spring of 2008 – Guillermo Canas had already fractured his dominance there a year earlier – and the clay season, although he managed to snag his first title of the year in (idyllic) Estoril. The talk of decline had commenced, and it has never stopped, although it periodically swells to a roar and recedes to a mutter, seasonally and comfortingly. He was beaten by Nadal in the Hamburg final, and then scourged by him at Roland Garros. A month later Nadal took his Wimbledon title, and with it, before long, the No.1 ranking. Federer had reigned for 237 consecutive weeks, eclipsing Jimmy Connors’ old record by 77 weeks.  Although a measure of redemption came when he won his fifth US Open title, he finished the year at No.2, and only ten points clear of Djokovic. The discourse of decline was inescapable, and conducted at a bellow.

Although a measure of redemption came when he won his fifth US Open title, he finished the year at No.2, and only ten points clear of Djokovic. The discourse of decline was inescapable, and conducted at a bellow.

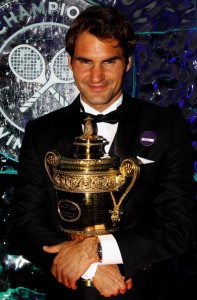

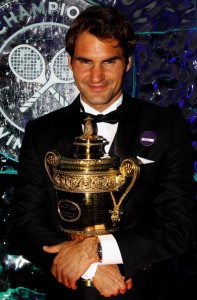

Federer reclaimed the No.1 ranking 46 weeks after it was torn away, not for the last time discovering it to be nicely packaged with a recovered Wimbledon trophy and the all-time record for major titles. He finished 2009 as No.1 for the fifth time, and became the second man in the Open Era to reclaim the year end No.1 spot (Ivan Lendl did it in 1989, while Nadal later achieved it in 2010). Federer would extend that lead by winning the Australian Open at the beginning of 2010. But two losses from match point up in the US Spring, as well as upsets to Albert Montanes and Ernests Gulbis on clay would have serious ramifications. Winning any one of those matches might have meant his ranking would survive the subsequent loss to Robin Soderling at Roland Garros, at least until Wimbledon. (This quarterfinal loss also halted Federer’s record run of consecutive major semifinals at 23, which is probably the most astounding of his obscure records.)  Federer was stranded on 285 total weeks at No.1. Pete Sampras held the record on 286 weeks. If it had ended this way, it might have remained poetic in its imperfection, akin to Sir Donald Bradman getting out for a duck in his final innings, and ending his Test career with an average of 99.94.

Although Federer would go on to lose in the quarterfinals of Wimbledon, and heartbreakingly in the semifinals of the US Open to Djokovic, he would end 2010 with a dominant display indoors, with titles in Stockholm, Basel and in London at the Tour Finals. On the face of it this little run seems inconsequential, but it ultimately proved invaluable. Federer’s latest return to the No.1 ranking finally happened at Wimbledon a week ago, after a gap of over two years, but the foundations were laid at the end of 2011, as he endured the entire European indoors without defeat, including a maiden title at the Paris Masters, and a record sixth at the Tour Finals.  These were augmented this year with Masters titles in Indian Wells and Madrid, as well as 500-level trophies in Rotterdam and Dubai, where he apparently had no other purpose than to ruin Juan Martin del Potro’s year.

These were augmented this year with Masters titles in Indian Wells and Madrid, as well as 500-level trophies in Rotterdam and Dubai, where he apparently had no other purpose than to ruin Juan Martin del Potro’s year.

If Federer ends this year as the No.1 player, it will be the sixth time he has done so. It isn’t even particularly unlikely, given that he has far fewer points to defend than Nadal or Djokovic during the US Summer, and has amply demonstrated his unsurpassed indoor prowess. Having said that, the last few months have proved that not only can anything happen, it usually will. Still, any men who insisted that this could happen following the US Open last year would have been ritually humiliated at some length, before being chemically castrated lest their moronic genes be passed on to others. Now who’s laughing? Probably not those guys. In fact, Federer was ranked No.4 behind Andy Murray as recently as last November, which he spent airily dismissing the Scot’s recent domination of the Asian swing. To his innumerable detractors, it seemed clear that the accelerating decline had well and truly ascended to a frenzy of sour grapes (which when left too long in the sun foments, and can be supplemented with fruit to form a kind of undrinkable, spritzy Sangria).

I will resist the temptation to extend and sustain the wine metaphor any further. A lesser man would cave, and lunge for the easy champagne reference. Indeed, to do so would be entirely in keeping with Federer’s bio that appears on the ATP website, which asserts that he has ‘a flair for aesthetics and class,’ whatever that means. Knowing that line was probably written with a straight face only makes it harder to maintain one while reading it. Among other things, Federer’s greatness makes him the easiest of athletes to wax hyperbolic about, a trap countless greater and lesser scribes have willingly hurled themselves into. But beyond the hosannas and panergyrics, it is hard for anyone writing about him not to fall back on the endless numbers. Like him or not, it takes a certain calibre of wilfulness to pretend these don’t add up to something quite imposing, if not magnificent. And beyond the fives and sevens and seventeens, the largest and latest number is 287, and it is made up of lots and lots of ones.

Or perhaps it’s fairer to assert the obverse, that the Olympics works well as a tennis tournament. So far the Olympic tennis event has looked and felt rather like a Masters event, which is gratifying for those of us who fervently believe one of those should be played on grass.

Or perhaps it’s fairer to assert the obverse, that the Olympics works well as a tennis tournament. So far the Olympic tennis event has looked and felt rather like a Masters event, which is gratifying for those of us who fervently believe one of those should be played on grass.