Stockholm, Second Round

The news came in last night (over the wire) that Australia has secured a non-permanent place on the United Nations Security Council. For months we have been warned by a succession of government ministers that this was unlikely to come to pass, given that Australia had entered the race relatively late in proceedings, while our main competition – Luxembourg and Finland – had been lobbying vigorously for the better part of a decade. There were only two ‘available’ seats, and Luxembourg secured one. Australia took the other from the fancied Finns. This happened just days after Lleyton Hewitt defeated Jarkko Nieminen at the If Stockholm Open. Australian-Finnish relations have consequently attained an all-time low.  There’s talk of invasion. Now that we’re on the Security Council, I assume we have that kind of power.

There’s talk of invasion. Now that we’re on the Security Council, I assume we have that kind of power.

(Actually, while it has generally been assumed that securing this seat is an incontrovertibly good thing, and it probably is, now that it has actually happened people are wondering why this might be so. Meanwhile those prone to wringing their hands have commenced wringing. One local radio commentator queried how we can presume to pontificate on the world stage without having our own house in order, thus betraying a stunning misunderstanding of what the Security Council is, given that it counts China, the USA and Russia among its permanent members.)

Stockholm numbers among my favourite 250 level tournaments. Along with Basel’s sadly missed confected pink courts, Stockholm seems quintessentially of the European Indoors. But if Basel’s new blue is generic, and an unneeded concession to London’s O2 Arena, Stockholm’s old blue is pervasive and oddly gloomy, as though the powerful floodlighting hasn’t alleviated the darkness so much as tinted it. From my remote Australian vantage, even the air looks saturated by it, as though the action is occurring underwater, or very far away but hurtling towards me, like the advance guard of Finland’s ground assault. It also has a trophy that looks like a doomsday device. You cannot get more European Indoors than that.

The second seed in Sweden this week is Tomas Berdych, who two weeks ago sought to defend his Beijing title in Tokyo. The top seed is Jo-Wilfried Tsonga, who is working a similar trick by endeavouring to defend his Vienna title in Stockholm. Stockholm’s defending champion is Gael Monfils, but he isn’t playing anywhere any more, having lost in the first round.  He has already committed the remainder of the season to convalescence. He’ll be back in the New Year, presumably as exciting, fragile and infuriating as ever. Anyway, the top two seeds are still there, and are ‘easing through’ the draw with a minimum of fuss. I’m especially looking forward to Berdych’s next match against Mikhail Youzhny, even if the latter has defied my advice by shaving his beard off again.

He has already committed the remainder of the season to convalescence. He’ll be back in the New Year, presumably as exciting, fragile and infuriating as ever. Anyway, the top two seeds are still there, and are ‘easing through’ the draw with a minimum of fuss. I’m especially looking forward to Berdych’s next match against Mikhail Youzhny, even if the latter has defied my advice by shaving his beard off again.

Otherwise today Marcos Baghdatis ‘eased past’ Alejandro Falla in only nine games, for the loss of none. The Columbian was injured, and wasn’t playing especially well even before he stopped playing entirely halfway through the second set. Straight after that Sergei Stakhovsky ‘eased past’ Feliciano Lopez – who looked strikingly misplaced in the luridly azure gloom – in a couple of tight sets. I still haven’t worked out precisely what ‘eased’ means, so I’m going to apply it to nearly everything just to be sure. From what I can tell, this is only the second time Stakhovsky has eased past the second round at tour level this season. Now that he has reached a quarterfinal, he might be interested to discover that his prize money will go up. He’ll certainly be interested to discover that he’s playing Tsonga.

Vienna, Second Round

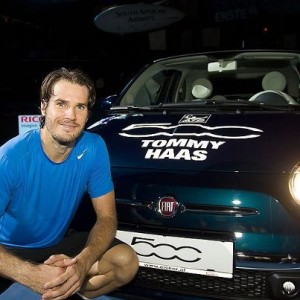

Meanwhile in Austria, in the timeless Vienna that Tsonga abandoned, Tommy Haas has become just the fourth active player to reach 500 wins on the ATP Tour.  The other three are Roger Federer, Rafael Nadal and former Young Australian of the Year Lleyton Hewitt, who will command his nation’s military forces for the coming Finnish campaign. Haas is the 38th man to reach this milestone in the Open Era. I won’t list all the others, but you can have a go if you like. Perhaps turn it into a parlour game.

The other three are Roger Federer, Rafael Nadal and former Young Australian of the Year Lleyton Hewitt, who will command his nation’s military forces for the coming Finnish campaign. Haas is the 38th man to reach this milestone in the Open Era. I won’t list all the others, but you can have a go if you like. Perhaps turn it into a parlour game.

The tournament gifted Haas a Fiat 500 to commemorate his 500th victory, with the ATP’s logo and ‘500 Tommy Haas’ emblazoned on the bonnet. The German is rightfully proud of his achievement: ‘It makes me really proud and for sure this is one of my biggest achievements after everything that happened. The fact that it happened here in Vienna makes it very special. Getting such a gift on top of it makes it an amazing day for me.’ But I wonder if he’s proud enough to cruise around in his new Fiat without having it repainted. There’s pride, but there’s also feeling like an idiot.

For the record, his 500th win came quite easily against Jesse Levine, over five years after his 400th, which was against Agustin Calleri in Montreal 2007. It’s been a tough five years. I also can’t help but wonder what the contingency plan was had Haas somehow lost to Levine. Would the Fiat have followed him to his next tournament, which is Valencia, and would receiving it have been quite as special there? So many questions, fated to remain unanswered. Here’s another: what if Haas then embarked on a sustained losing streak worthy of Donald Young? The Fiat might come to feel like a rather bad omen. Perhaps they’d just change the 500 to a 499 and give it to him anyway, to bolster his spirits. Does Fiat make a 499?