Hopman Cup

Murray d. Mahut 7/6 7/6

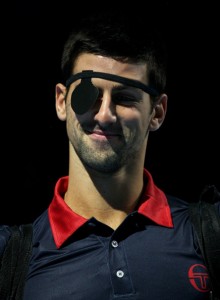

Lleyton Hewitt was back in the commentary booth last night, and so was ‘tremendous ball striking’. But that wasn’t the strangest thing he said. Invited to analyse his loss to Novak Djokovic – in which he went down 6/2 6/4 – Hewitt waxed earnest on how extremely well he’d struck the ball, how extremely well he’d moved, how extremely well he’d competed. (‘Extremely well’ is clearly a verbal tic for Hewitt, a catch-all suffix whose relentless use nonetheless reflects his determination to have nothing but kind things to say, even about himself. Murray was ‘moving extremely well’. Mahut was ‘competing extremely well’. Both of them were ‘striking the ball extremely well’. Sadly, ‘extremely well’ precludes the use of ‘tremendous’.) This is despite the fact that Hewitt won exactly half as many games as Djokovic, and that despite earning a fistful of break points, it wasn’t especially close. If he’d made his comments before the match, then been cleaned up 2 and 4, the irony might have been poignant. Coming afterwards, it was just a little deluded. Hewitt, a veteran whom the race has outrun, is coming to seem less Learesque in his impotence, and more like Don Quixote, or Eddie the Eagle.

Lleyton Hewitt was back in the commentary booth last night, and so was ‘tremendous ball striking’. But that wasn’t the strangest thing he said. Invited to analyse his loss to Novak Djokovic – in which he went down 6/2 6/4 – Hewitt waxed earnest on how extremely well he’d struck the ball, how extremely well he’d moved, how extremely well he’d competed. (‘Extremely well’ is clearly a verbal tic for Hewitt, a catch-all suffix whose relentless use nonetheless reflects his determination to have nothing but kind things to say, even about himself. Murray was ‘moving extremely well’. Mahut was ‘competing extremely well’. Both of them were ‘striking the ball extremely well’. Sadly, ‘extremely well’ precludes the use of ‘tremendous’.) This is despite the fact that Hewitt won exactly half as many games as Djokovic, and that despite earning a fistful of break points, it wasn’t especially close. If he’d made his comments before the match, then been cleaned up 2 and 4, the irony might have been poignant. Coming afterwards, it was just a little deluded. Hewitt, a veteran whom the race has outrun, is coming to seem less Learesque in his impotence, and more like Don Quixote, or Eddie the Eagle.

This unintended irony persisted even after Hewitt left. There’s an affliction known as the Commentator’s Curse, whereby complimenting a player on an aspect of their game will inspire an immediate if temporary drop in execution. For example, pointing out that someone is serving well might produce a double fault. Following Hewitt’s example, Paul McNamee and Josh Eagle set out to confound this specious causality. A Murray double fault provoked the (non-ironic) statement that he was serving well. A 27 stroke rally that Murray concluded by meekly dumping a sliced backhand into the net inspired Eagle to remark on how much variety Murray brought to the game, how effective he was at changing paces. Even McNamee found this confusing, although not as confusing as his subsequent remark: ‘Yes, 27 shot rally. He’s world No.4.’

Otherwise, the commentary was about what you’d expect. A mishit winner from Mahut produced a perfunctory apology from the Frenchman, which in turn inspired the standard ponderous levity from the commentators (Hewitt included): ‘He’s apologising, but I’ll bet he’ll take it. Ho ho ho.’ Hewitt might have pointed out that when players do this they aren’t apologising, but conceding to their opponent that they won the point through good fortune. A clutch Murray serve to save break point was ‘quality’, while a Mahut forehand was ‘class’. The missing word in both cases was ‘high’. Applied to the commentary, however, the missing word was ‘low’. One of Murray’s backhands was struck ‘extremely well’ and with ‘tremendous direction’.

Otherwise, the commentary was about what you’d expect. A mishit winner from Mahut produced a perfunctory apology from the Frenchman, which in turn inspired the standard ponderous levity from the commentators (Hewitt included): ‘He’s apologising, but I’ll bet he’ll take it. Ho ho ho.’ Hewitt might have pointed out that when players do this they aren’t apologising, but conceding to their opponent that they won the point through good fortune. A clutch Murray serve to save break point was ‘quality’, while a Mahut forehand was ‘class’. The missing word in both cases was ‘high’. Applied to the commentary, however, the missing word was ‘low’. One of Murray’s backhands was struck ‘extremely well’ and with ‘tremendous direction’.

The match itself was very good, and highly entertaining. Mahut can be up and down, a tendency French players apparently acquire at their mother’s teat. He was only ever up until he had break points, or set points, but when he was up he was typically engaging. He backspun one drop volley so sharply that it nearly returned to his side of the court. Josh Eagle was correct in highlighting just how impressive it was. Twice Mahut ended up on Murray’s side of the court. The second time he nearly took the Scotsman out, but it was all in good fun. Murray tried a tweener like the one Federer hit in Doha the other night, but found the tape.