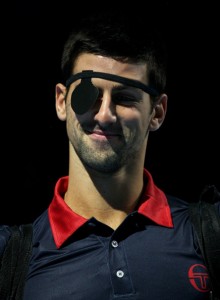

If beating compatriot Victor Troicki at the US Open was on par with sleeping with his girlfriend, one can only imagine the pleasure Novak Djokovic felt as he watched Troicki trounce Michael Llodra to clinch the Davis Cup. Still dozily basking in the afterglow of that triumph, it will probably be a tough sell convincing him he’s really had a pretty poor year.

Let’s consider it. What if Troicki had fallen to Llodra in the year’s final match? How would Djokovic’s 2010 look then? He spent almost exactly half the year at No.2, but that was achieved primarily by Nadal then Federer hemorrhaging large point-hauls. They’ve since staunched themselves, and Djokovic finds himself 3,000 points adrift at No.3. Leaving the US Open aside for the moment, his results were unsatisfactory when it mattered; at the Slams, and at the Masters where he is usually so intimidating. He has claimed only two titles – 500 events in Dubai and Beijing – his lowest return since 2006.

Let’s consider it. What if Troicki had fallen to Llodra in the year’s final match? How would Djokovic’s 2010 look then? He spent almost exactly half the year at No.2, but that was achieved primarily by Nadal then Federer hemorrhaging large point-hauls. They’ve since staunched themselves, and Djokovic finds himself 3,000 points adrift at No.3. Leaving the US Open aside for the moment, his results were unsatisfactory when it mattered; at the Slams, and at the Masters where he is usually so intimidating. He has claimed only two titles – 500 events in Dubai and Beijing – his lowest return since 2006.

Still, if it has been a bad year, it’s at least been trending encouragingly upward. The second half – starting from Wimbledon but excluding that fan-crushingly weak semifinal – has witnessed vast improvements. He has progressed from regular losses to solid second-tier players (Tsonga, Youzhny) and the odd shocker (Malisse, Olivier Rochus), to falling almost exclusively to top shelf opposition. It is progress, to be sure, but it’s illustrated just how far he still has to go. Of the seven losses he has suffered since Wimbledon, four have been to Federer and one to Nadal. In none of the matches were the stakes negligible, and in few of them did he look especially dangerous. So while Djokovic in a Fedal-free draw evokes Gulliver in Lilliput, that’s never going to be the case in the big events, where the top two have mastered the art of showing up, and have made it synonymous with winning.

The US Open semifinal is of course the towering exception. But it was a strange encounter, and did little to refute Federer’s putatively arrogant assertion that these matches are always more or less on his racquet. (For parts it followed a regular script between these two, in which Djokovic appears to be the slightly better player, only to crumble at the death of each set.  It is fascinating how often Federer claims their sets 7/5.) It was a famous win for the Serb, almost worthy of his wide-eyed histrionics after match-point, but Nadal lurked in wait. As with Murray in Melbourne, Soderling in Paris, and Berdych in London, in order to claim a major title Djokovic needed to beat Federer and Nadal. Only one man has ever done that (del Potro), which goes a long way towards explaining why the Big Two – the Brobdingnagians – own 25 of the last 30 Slams.

It is fascinating how often Federer claims their sets 7/5.) It was a famous win for the Serb, almost worthy of his wide-eyed histrionics after match-point, but Nadal lurked in wait. As with Murray in Melbourne, Soderling in Paris, and Berdych in London, in order to claim a major title Djokovic needed to beat Federer and Nadal. Only one man has ever done that (del Potro), which goes a long way towards explaining why the Big Two – the Brobdingnagians – own 25 of the last 30 Slams.

Against lesser opposition Djokovic can look almost invincible. The Davis Cup final showcased this perfectly. Djokovic was like a juggernaut, and the French team’s entire strategy was little short of a tacit admission that they wouldn’t be taking any matches from him. It was containment, pure and simple. Llodra was protected from him, Simon was sacrificed to him, and Monfils, um, well I don’t quite know what the plan was there.

I’ve previously anointed Robin Soderling as the ‘best of the rest’, but that view depends on where you begin your definition of ‘the rest’. There is a lot to be said for beginning ‘the rest’ with Djokovic. The ATP website is running a puff piece posing the seaching question of whether the Serb will be the man to finally break the Federer-Nadal duopoly. It predictably adds little to the discussion, and in lieu of a conclusion opts for some threadbare stuff on how hard Djokovic is working and how badly he wants it. Ho-hum. There is of course no answer – this is sport – and the question was barely worth asking. The only answer is that Djokovic’s hard work and burning desire have pushed him to a glass ceiling. Breaking through it will require something extra, something transcendent, even paroxymal. Something orgasmic. If he wins the Australian Open, his girlfriend will have her work cut out topping that.

2 Responses to Gulliver in Lilliput