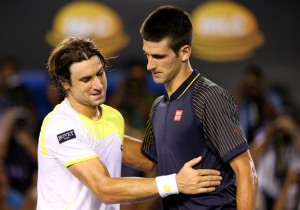

Australian Open, Semifinal

(1) Djokovic d. (4) Ferrer, 6/2 6/2 6/1

‘I am trying to do my best every match, but I know they are better than me. What can I do?’ – David Ferrer.

In some ways, it felt appropriate that David Ferrer won just five games in his semifinal against Novak Djokovic tonight. That’s exactly how many games he won against Rafael Nadal in the semifinal at Roland Garros last year. If you’re going to get blown away, you might as well establish a pattern. Everyone loves a pattern. It creates the seductive illusion of meaning, and encourages us to concoct a narrative.  The narrative in this case is that Ferrer, the sport’s most dogged underdog, fights his heart out but is simply outclassed on the biggest stages: ‘But I know they are better than me. What can I do?’ Isn’t he adorable?

The narrative in this case is that Ferrer, the sport’s most dogged underdog, fights his heart out but is simply outclassed on the biggest stages: ‘But I know they are better than me. What can I do?’ Isn’t he adorable?

Djokovic’s ownership of Rod Laver Arena isn’t yet as secure as Nadal’s of Court Philippe Chatrier, although based on tonight’s near-perfect performance it isn’t beyond imagining that it soon will be. He didn’t look like he’ll be losing any time soon, although whoever he faces in the final will almost certainly provide a stiffer challenge than Ferrer did. At the very least, we can assume they’ll put up a fight.

The most lavishly applied term, at least in American coverage of Ferrer’s matches, is ‘respect’. The prevailing vibe is that the Spaniard receives nowhere near enough of it, although as far as I can make out this crippling deficit frustrates the commentators more than the player himself. When probed, he generally waves the issue away. Nonetheless, expect ESPN to announce a twenty-four hour telethon for his benefit, whereby concerned viewers may call in and pledge some respect of their own (not too much, mind, but every little bit helps, and it’s all tax-deductible). Indeed, there seems to be consensus that not only is Ferrer not respected enough, he is actively ‘disrespected’, which has come to mean far more than the mere absence of respect. Apparently it’s worse.

Given my anachronistic determination to go on using the many subtly-shaded words that English already had before ‘disrespect’ became a force – disregard, irreverence, insolence, impudence – I am unqualified to judge how much disrespect Djokovic directed towards his opponent tonight. Did he not respect him enough, or did he disrespect him too much? Some suggested that by thrashing Ferrer so vehemently, Djokovic showed enormous respect. The line of reasoning is that the world No.1 brought his best game to bear precisely because of the threat posed by the Spaniard (with the implication being that he would have chosen to play worse if facing an opponent he respected less, or disrespected more). If this is true, it surely explains why Ferrer is reluctant ever to engage with the matter when it’s raised. If this is what respect feels like, he can probably cope with less of it, not more. He’d already experienced Nadal’s respect at last year’s French Open, and he couldn’t sit down for a week afterwards.

Ferrer’s genuine humility invites all this concern, and there’s a case to be made that the ‘disrespect’ allegedly broadcast at him takes its cue from the deprecation he expresses towards his own game. Lleyton Hewitt in commentary told an excellent story – he is always valuable when he eschews trite analysis in lieu of the type of specific detail available nowhere else – that revealed just how winsomely diffident Ferrer can be. A few years ago, but recently enough that it falls within the Spaniard’s hey-day and the Australian’s long twilight, Ferrer wanted Hewitt to sign his Davis Cup shirt. However, Ferrer was too shy to ask Hewitt himself, notwithstanding that he was himself a fixture in the top ten, while Hewitt was struggling to reconcile a professional tennis career with his passion for surgery. Instead Ferrer put it to Hewitt’s Spanish-speaking physio, who relayed it on. Hewitt admitted to being taken aback. (For the record, he did sign the shirt.) There is no shortage of respect for Ferrer amongst the tour players, and he is, by all accounts, hugely admired.

Among non-players, however, the main term I’d use is ‘patronise’. Too much respect can be fatal, especially as tonight when it comes on inexorably like a tsunami. But to be patronised endlessly is to experience the slow suffocation of lowered expectations. Tonight’s semifinal was pitifully uncompetitive, and my problem with it was that no one appeared  to expect more. Too many shrugged, tossed about some canine metaphors, and pronounced themselves satisfied. But Ferrer is currently the world No.4, and the fourth seed, playing a Major semifinal. Just because he’s a nice guy doesn’t mean he gets a free pass for submitting to a hiding. If Djokovic was too good, why didn’t Ferrer try to make him play worse? Why didn’t he try something?

As the third set commenced, Hewitt, in strong anecdotal form, recalled the parallel moment during his loss to Djokovic here last year in the fourth round. He related that when down two sets and being hustled all over and off the court, he broke the contest down into its constituent elements. He simply focussed on holding his own serve at the cost of everything else, so that he could at least feel like he was ahead in that set. Then he could see what might transpire. What did transpire was that he came back to win the third set, as the unexpected stoutness of his defence caused Djokovic momentarily to waver. The sheen in his eyes as he turned to his box suggested that this one set meant more to him than any number of victories had. Naturally, Djokovic is far too good to allow this to continue, and he’s a far better player than Hewitt, and so came back to win the fourth. While Hewitt was relating this, Ferrer was perfunctorily broken to open the third, his game unmodified from the first two disastrous sets. The contrast was perfect.

In truth, Hewitt made far more adjustments in last year’s match than simply focussing on his serve. He stepped up into the court and refused to yield the baseline, and began to employ his slice more often and more variously. He lured the world No.1 into the net, and passed and lobbed him. In short, he tried everything he conceivably could. We can point to match-ups all we want. It’s undeniable that Djokovic is a terrible match-up for Ferrer, but he’s hardly a better prospect for Hewitt. Yet twice last year Hewitt fought his heart out to grab sets from Djokovic, and at the Olympics nearly delivered an audacious upset.

Tonight Ferrer played the third set the way he played the others, with a near-pristine lack of imagination, and a perfect willingness to be dictated to. Upon delivering first serves he would immediately retreat to the Melbourne sign metres beyond the baseline, whereupon he would commence running, and be prodded into locations from which he couldn’t penetrate. Djokovic’s form was imperious, but with his opponent scurrying backwards there was no reason for it not to be.

Obviously, it might not have made any difference whatsoever. Players have attempted any number of creative approaches to save a dying cause, but to no avail. When Tommy Haas was demolished by Fernando Gonzalez in the 2007 Australian Open it wasn’t because the German lacked imagination. Gonzalez was simply unplayable. It happens, and although Haas left the court feeling he hadn’t played especially well, he at least knew he’d tried everything he could have. In a Major semifinal, especially if you’ve never progressed beyond it, there’s no reason not to try everything.

It could be that I’m alone in this, but I thought Ferrer’s endeavour was entirely inadequate, as were his responses when questioned afterwards. Of course he ran. He always runs, but running endlessly is not the same as fighting, and too readily are the two confused. His assertion that Djokovic had simply been too good – ‘I didn’t have any chance for to win tonight’ – has been greeted rather indulgently and pityingly, as though it is self-evidently true. Perhaps Djokovic was too good – he was very, very good – but the last person who should accept that is his opponent. If Ferrer gains too little respect, I don’t think his effort tonight merited more, and it’s easy enough to be humble when you’ve just been humiliated. He’s supposed to be a fighter. Where was the fight?

4 Responses to An Established Pattern