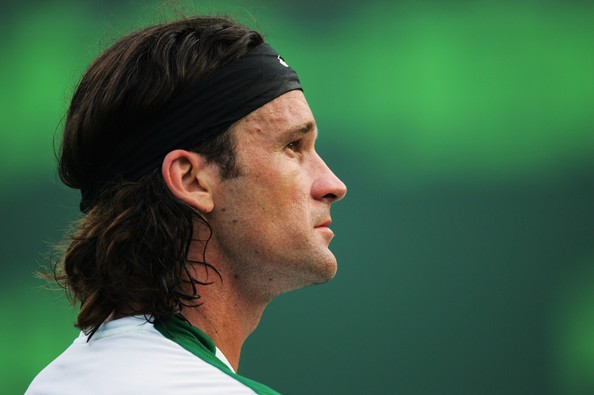

34-year-old Carlos Moya this week announced his retirement from professional tennis, citing a lingering right foot injury as the main culprit, although surely being 34 is reason enough. He leaves the game with a single Grand Slam title (1998 French Open), a Davis Cup (2004), 3 Masters Series shields, and an overall match record of 575-319 (.643).

34-year-old Carlos Moya this week announced his retirement from professional tennis, citing a lingering right foot injury as the main culprit, although surely being 34 is reason enough. He leaves the game with a single Grand Slam title (1998 French Open), a Davis Cup (2004), 3 Masters Series shields, and an overall match record of 575-319 (.643).

Reducing a rich and varied career to a few scattered moments is, inevitably, an act of traducement, even with the best intentions in the world. But anyway, here are some of my favourite moments from a decade and a half of watching Moya play:

Moya’s loss to his one-time protege, good friend and fellow Mallorcan Rafael Nadal in the 2008 Chennai semifinal, after holding four match points in the second set tiebreaker. I won’t go into the detail too much, since this match is the subject of an upcoming Great Matches You’ve Probably Never Heard Of entry. As you might expect, it was a supremely physical encounter, and both men held little back, despite the fact that almost nothing significant was riding on the outcome. Moya was 31, and Nadal at 21 was already in his prime, although he was clearly not yet the hardcourt force he has since become. Moya’s effort was a succinct demonstration, if any more were needed by this late date, that he was a very fine hardcourt player, and that his run to the Australian Open final 11 years earlier was nowhere near as startling as his failure to achieve anything comparable in the long years since.

Moya’s defeat of Lleyton Hewitt at the 2001 Australian Open, which the Spaniard won 7/5 in the fifth. This was a titanic struggle, a heated night encounter conducted in an atmosphere of virulent nationalism (Spain had beaten Australia in the Davis Cup final the month before, although Moya had played no part in that). Hewitt had survived a spiteful encounter with Jonas Bjorkman the round before and there was a strong feeling that this was the year for Hewitt to Go All The Way. In the end Moya held his nerve admirably, even as his backhand began to collapse, and even as his famous reserve showed cracks in the face of the Australian’s characteristic antics.

The 1997 Australian Open. I tend to remember Moya’s semifinal trouncing of second seed Michael Chang more than the final, in which he was flogged by a rampant Pete Sampras, to no one’s surprise. Chang is not an easy man to beat on a slowish hardcourt, and the 21 year old Moya displayed fabulous poise. The main feature, however, was his forehand. I’d never seen a stroke with a trajectory quite like it, the way the viciousness of the topspin would bring it down at the last possible moment, and cause it to rear steeply off the rebound ace. In the pre-Nadal era, Moya’s forehand was as heavy as any. It was a tangible evolutionary stage in the power-baseline game.

The 2003 French Open. This tournament is remembered for any number of reasons. It remains Ferrero’s only title at Roland Garros, despite the widespread certainty that he  would go on to dominate. There was Guillermo Coria’s notorious moment of madness in the semifinal, when he cracked and hurled his racquet in rage, only to almost get defaulted when it grazed a ballkid. And of course there was Dutchman Martin Verkerk’s supremely improbable run to the final. It was his five-set upset of Moya in the quarters that is most pertinent here. As an accomplished dirtballer in excellent form, Moya was among the clear favourites for the title. Verkerk was not accomplished on any surface, but clay was particularly ill-suited to his game, with his ungainly groundstrokes, pedestrian top-speed, and a capacity to change direction roughly on par with a crude-oil tanker. After 1998, Moya never again made it past the quarterfinals at another Grand Slam, which is a shocking stat for a player of his ability and fitness. This heartbreaking loss to Verkerk made it clear that there was a structural deficiency somewhere in Moya’s approach to the big events. I mean really, Martin Verkerk?!

would go on to dominate. There was Guillermo Coria’s notorious moment of madness in the semifinal, when he cracked and hurled his racquet in rage, only to almost get defaulted when it grazed a ballkid. And of course there was Dutchman Martin Verkerk’s supremely improbable run to the final. It was his five-set upset of Moya in the quarters that is most pertinent here. As an accomplished dirtballer in excellent form, Moya was among the clear favourites for the title. Verkerk was not accomplished on any surface, but clay was particularly ill-suited to his game, with his ungainly groundstrokes, pedestrian top-speed, and a capacity to change direction roughly on par with a crude-oil tanker. After 1998, Moya never again made it past the quarterfinals at another Grand Slam, which is a shocking stat for a player of his ability and fitness. This heartbreaking loss to Verkerk made it clear that there was a structural deficiency somewhere in Moya’s approach to the big events. I mean really, Martin Verkerk?!